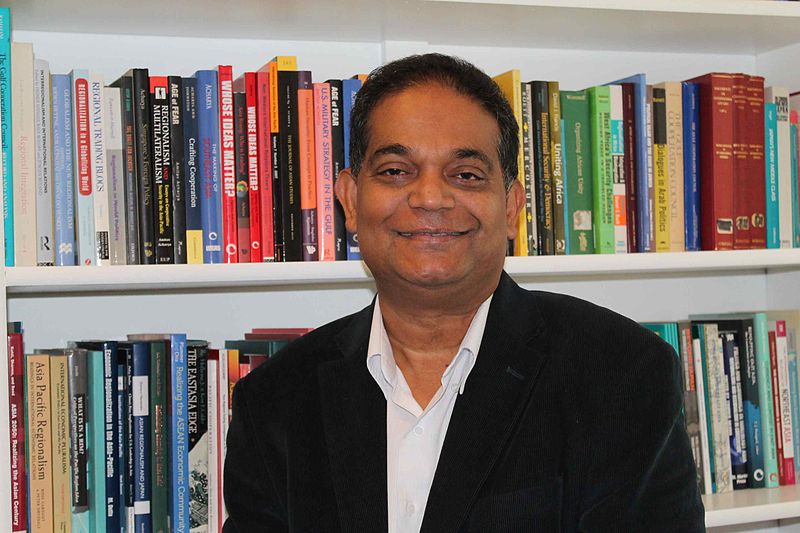

Fonte: Wikimedia.

Nesta semana, o Observatório de Regionalismo publica a entrevista realizada com o Professor Dr. Amitav Acharya, Professor Emérito de Relações Internacional na American University, Washington DC, Berggruen Institute Fellow no período 2019-2020 e ex-presidente da Associação de Estudos Internacionais no período 2014-2015. O Professor Acharya comentou sobre a crise global e seus impactos na Ásia e África, a relevância do regionalismo comparado como instrumento analítico e como superar o colonialismo, especialmente nas Relações Internacionais. O Professor Acharya foi entrevistado por Julia Borba durante o VI Congreso RedIntercol

(This week, the Regionalism Observatory shares an interview with professor dr. Amitav Acharya, distinguished Professor of International Relations at the American University, Washington DC, Berggruen Institute Fellow for 2019-2020 and the former president of the International Studies Association (ISA) for 2014-15. Professor Acharya commented on the global crisis and its impacts on Asian and Africa, the relevance of comparative regionalism as an analytical device and how to overcome colonialism, especially in the IR field. Professor Acharya was interviewed by Julia Borba during the VI Congreso RedIntercol)

In times we are discussing the global order crisis and its influence over the regionalism crisis in Europe and Latin America, we also observe the regionalism in Africa and Asia responding to this global crisis by deepening its economic integration. What can we learn from the experiences of these two regions?

I think they are responding to it in very different ways. In my sense, Asia is responding more in terms of economic integration and Africa is not quite doing that, not in the same way. Africa is more committed to security cooperation than economic cooperation. In theory, there is a lot of initiatives in Africa but in practice, the level of integration is not as high and it has to do with the fact that the economic integration in Asia happens informally through the marketplaces and companies rather than through governments. In Africa, we have little transnational production networks, supply chains, so Africa in approach is actually trying to emulate the European Union and its institution’s development of mechanisms of free trade, as opposed to Asia where the private sector and the companies do a lot of integration themselves, through supply chains, through mobility of labor and technology. So I think Africa is not following Asia, at least in substance, but Africa is doing very well by promoting security programs, in which Asia is actually behind. So Asia is behind Africa in security cooperation and Africa is behind Asia in economic integration.

Why is the concept of comparative regionalism relevant in order to understand the current global scenario?

It is very important as an analytical device, for example, for regions that are not alike. The need of comparative regionalism came about because people realized that there was too much emphasis in the European Union and therefore the European Union’s life and history become the motto for everyone to follow, but regionalism is much broader and more complex and it happens in many different ways and paths. Comparative Regionalism is the way to understand the differences and similarities among different paths of regionalisms. So to understand the crises in regionalism, since no two regions are alike, you have to consider partly some global structural factors like the Trade War and deglobalization, but really partly has to do with the region itself: comparative regionalism allows us to understand the region’s specific factors, like what kind of politics, production systems, external interventions are there to understand the crisis in regionalism.

How colonialism and imperialism interfere in the scientific production and the local researchers’ perspectives in the peripheral regions?

By controlling the minds of the scholars, because we are told from a young stage that as Western ideas and culture are superior and Western institutions are more efficient so we develop an inferiority complex and a lot of scholars try to emulate the West, as opposed to critique the West. So it is a kind of control of the mind. It takes a while to overcome that with the help of post-colonial and decolonial literature, but that is not easy. I think that’s why History is so important: there is a very long and meaningful history of these cultures before colonialism came in, and it produces many benefits, but it’s something people don’t realize – so you need to bring that in. Everything I was talking today (at the VI Redintercol Congress) fits into that: how do you decolonize your mind as opposed to decolonizing the country.